RV inverter sizing is where most “my system keeps tripping” stories begin. Here’s the problem: you buy an inverter based on the biggest number on the box, you fire up the microwave, and boom—alarm, shutdown, or that sad little beep of regret. Then you waste a weekend swapping parts instead of camping.

Let me agitate this a bit: the inverter usually isn’t the villain. Your rig trips because surge demand spikes, battery voltage sags, or your cables act like skinny drinking straws when you need a fire hose. The fix is simple: size for real-world surge and design the whole system (battery + wiring + protection) like you actually want it to work.

Table of Contents

- 1) The fast way to size an RV inverter

- 2) Continuous vs inverter surge wattage

- 3) Pure sine inverter RV: when it matters

- 4) Inverter for microwave: what people miss

- 5) Inverter for AC: the honest requirements

- 6) Battery math that prevents trips

- 7) Wiring, fusing, and safety

- 8) The 7 mistakes that cause shutdowns

- 9) FAQ

- 10) My Top Recommended Gear

1) The fast way to size an RV inverter

Answer Target: Size your inverter by taking your largest load’s running watts and adding its startup surge, then add only the loads you’ll actually run at the same time. Choose a pure sine inverter RV for modern electronics, and ensure your battery bank and cable sizing prevent voltage sag. If you skip the battery/wiring side, you’ll still trip even with “enough watts.”

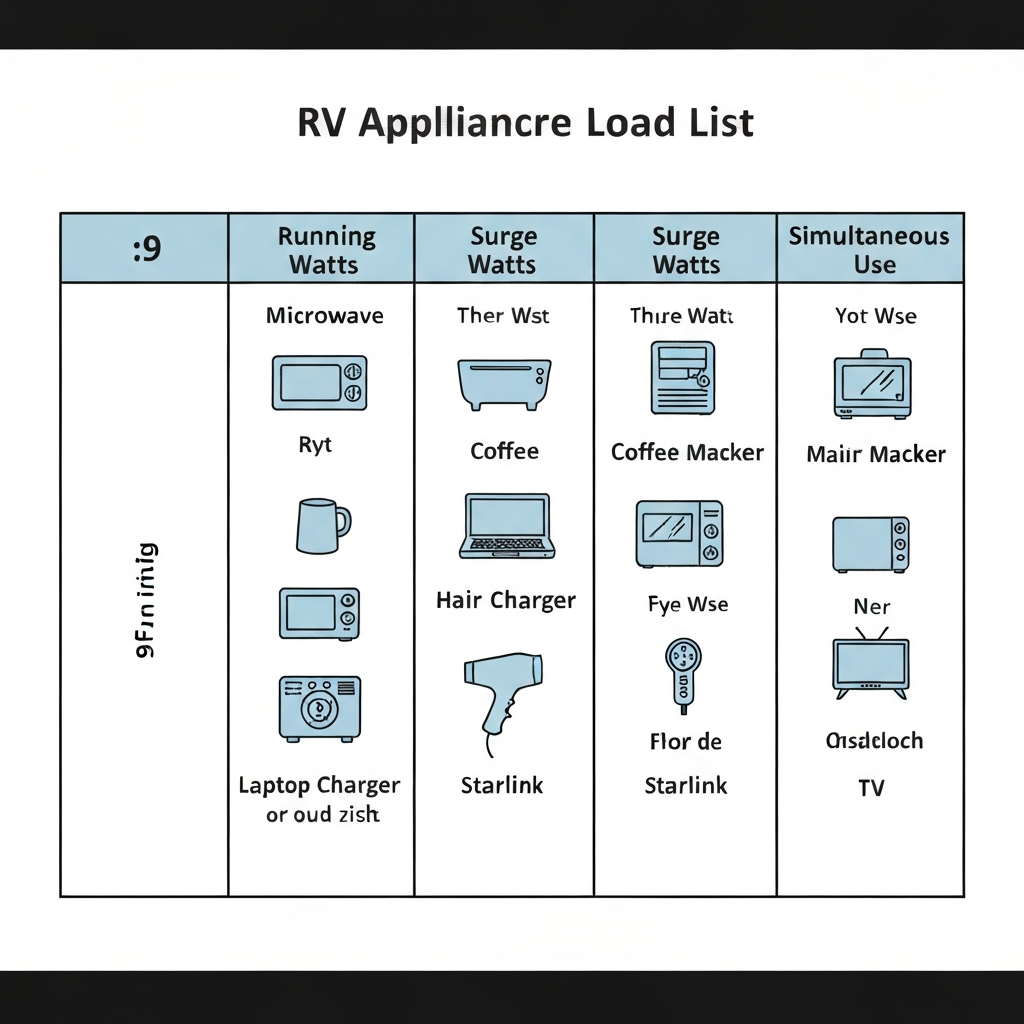

If you want a clean rule that works: list your top 5 AC loads, mark what runs together, and pick an inverter that covers the worst combo plus surge. I don’t mean “everything in the RV at once.” I mean your real habits: microwave + a couple chargers, or coffee maker + TV, or laptop + Starlink + lights.

For most rigs, here’s where you land:

- 1000W–1500W: Light duty (charging, TV, small kitchen stuff), but it’s easy to outgrow.

- 2000W: The “sweet spot” for a lot of people—strong general use, and it can handle many microwaves if the rest of the system is built right.

- 3000W: The “I’m done messing around” tier—better for heavier kitchen loads and gives you breathing room for simultaneous draws.

Now the punchline: your inverter is only one part of the stack. A great inverter paired with weak batteries and thin cables still trips. If you want a solid primer on what an inverter actually does (and why waveform matters), Wikipedia’s overview of power inverters gives the core concepts without marketing fluff.

Internal link note: plug your own related guide right here when ready—this is where it naturally fits. See my RV power system basics guide.

2) Continuous vs inverter surge wattage

This is the part most people get wrong because manufacturers love headline numbers. Your inverter has two key ratings:

- Continuous watts: what it can provide all day without overheating.

- Surge watts: short burst power for startup loads (motors, compressors, some microwaves).

Here’s the trap: surge ratings often last seconds. Some loads need a spike for longer than you think. If the inverter can’t sustain that surge long enough, it trips even though “surge watts” looked adequate. IMO, you should treat surge as “nice to have,” not “permission to undersize.”

Practical sizing logic:

- If your biggest load is a microwave, focus on real input draw and voltage sag (more on that soon).

- If your biggest load is a compressor (aircon, fridge compressor, etc.), focus on the startup event and consider soft-start tech.

- If you’re stacking multiple moderate loads, continuous watts matter more than surge.

For a quick reference on how AC power and appliances behave, the U.S. Department of Energy’s general electricity basics and power concepts are useful context: electricity basics from Energy.gov.

3) Pure sine inverter RV: when it matters

If you run modern electronics, I treat pure sine inverter RV as the default, not the upgrade. Modified sine can work for some resistive loads, but it can create annoying side effects: buzzing, extra heat, charger weirdness, or devices that refuse to run.

Here’s where pure sine matters the most:

- Microwaves: They can run hotter, noisier, or less efficiently on ugly waveforms.

- Medical devices: CPAP and similar devices deserve clean power.

- Battery chargers + power bricks: Some run warm or fail early on rough waveforms.

- Induction cooktops and anything “smart”: They tend to be picky.

Also, “pure sine” doesn’t automatically mean “good inverter.” Build quality, cooling, low-voltage cutoffs, and surge handling matter. But if you ask me what reduces headaches fastest, it’s pure sine.

Internal link note: a product roundup fits perfectly here. Check my best RV inverters shortlist.

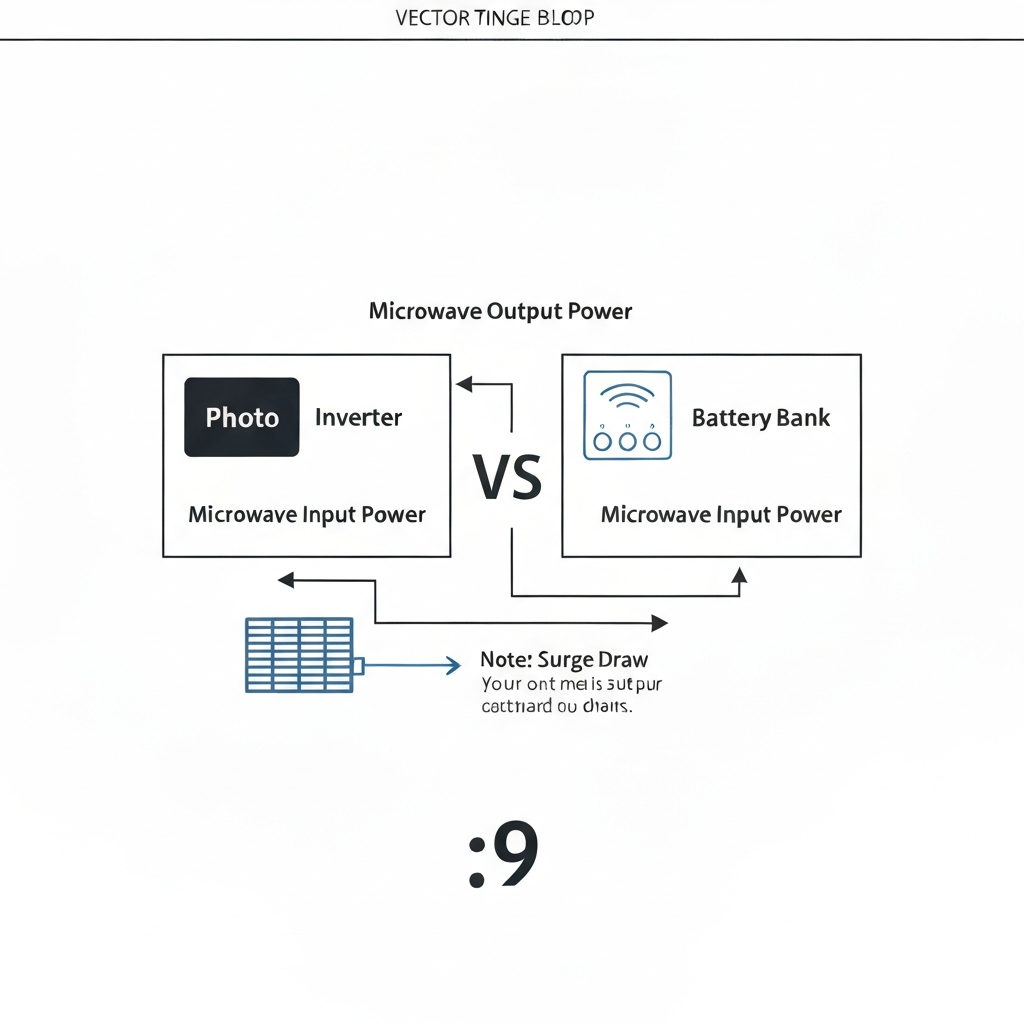

4) Inverter for microwave: what people miss

Let’s talk inverter for microwave, because this is the #1 reason weekend warriors rage-buy bigger inverters. Microwaves are sneaky: the “cooking power” (like 900W) is not the input draw. Many RV microwaves pull closer to 1300W–1700W input, and startup can spike above that.

What I do in the field (and what I recommend you do):

- Use the microwave’s input watts from the label or manual, not the “output cooking watts.”

- Assume extra overhead for inverter inefficiency (heat has to go somewhere).

- Plan for voltage sag if your battery bank is small or your cables are long.

Want a nerdy but useful reference point? Even Wikipedia’s microwave oven overview helps explain why these appliances behave differently than a simple resistive heater.

Here’s the no-drama sizing guidance for microwaves:

- Small microwave (input ~1200W–1400W): a good 2000W pure sine inverter often works if your batteries and cables are legit.

- Mid/large microwave (input ~1500W–1800W): 3000W gives you margin, less nuisance tripping, and less “don’t turn on anything else” babysitting.

And yes, you can “make it work” with less, but you’ll play inverter shutdown roulette. That gets old fast 🙂

5) Inverter for AC: the honest requirements

Inverter for AC is the dream. It’s also where sloppy systems go to die. Air conditioners have compressor startup surges that can dwarf running draw. If you try this with the wrong setup, the inverter trips, your batteries sag, and you cook cables you didn’t even know were underrated.

If you want inverter-driven aircon to be stable, you typically need:

- Soft start module on the air conditioner (this reduces startup surge dramatically).

- 3000W+ pure sine inverter with strong surge handling and real continuous capacity.

- A serious battery bank (not a single small lithium or a couple tired lead-acids).

- Correct cable gauge + short runs to prevent voltage drop.

Even then, runtime depends on battery capacity and ambient heat. For broader battery and storage fundamentals (which translate directly to RV setups), NREL’s battery storage resources are a solid sanity check: NREL battery storage basics.

Internal link note: this is a prime spot for your aircon power guide. Read my RV air conditioner power planning guide.

Pro Recommendation (ClickBank): Solar Safe

If you want a structured path to cutting generator time and building a real off-grid power plan, Solar Safe is a solid “systems thinking” shortcut. It focuses on solar fundamentals, load planning, and building an approach that doesn’t crumble the first time you run high-demand appliances.

Get Solar Safe (via ClickBank HopLink)

Note: This uses the standard HopLink format: affiliateNickname.vendorNickname.hop.clickbank.net with a tracking ID.

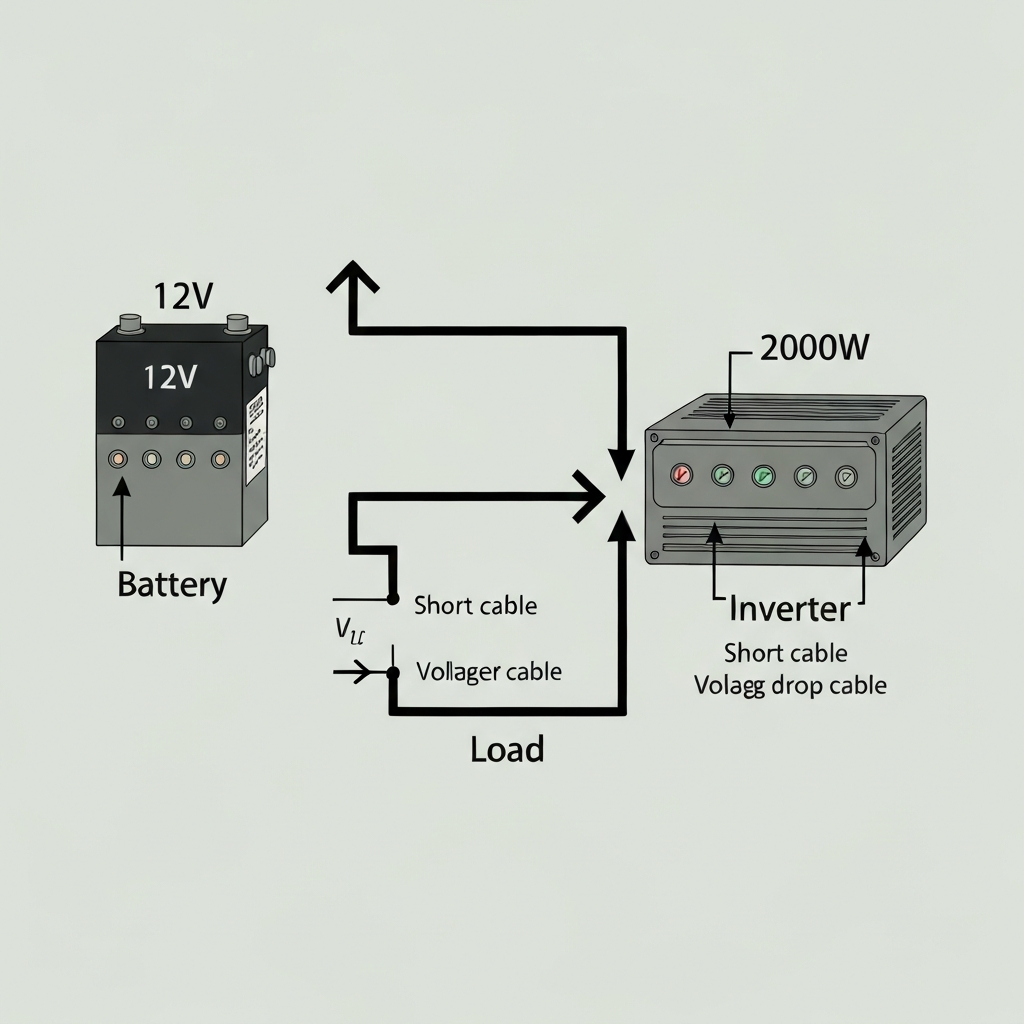

6) Battery math that prevents trips

Most “my inverter trips” complaints come down to voltage sag. The inverter doesn’t just need watts—it needs stable voltage under load. When voltage drops, current rises to deliver the same power, and the inverter hits low-voltage cutoff or protective limits.

Here’s the back-of-napkin math I use:

- DC amps ≈ AC watts ÷ (battery volts × efficiency)

- Example: 2000W ÷ (12V × 0.9) ≈ 185A

That’s a lot of current. At those levels, every weak link shows up fast: undersized cables, long runs, tired batteries, poor terminals, cheap lugs, loose grounds.

Two practical moves that instantly reduce trips:

- Go bigger on copper and shorter on distance. Thick, short cables reduce voltage drop and heat.

- Increase system voltage if your setup allows it. A 24V system halves current for the same power, which makes everything easier.

If you want a quick refresher on voltage drop principles (and why distance matters), Wikipedia’s overview of voltage drop explains the physics without selling you anything.

7) Wiring, fusing, and safety

I’m going to be blunt: big inverters without proper protection are a fire risk. I don’t care how “careful” you are—faults happen. Heat happens. Vibration happens. Build it like you want it to survive potholes, not just a driveway test.

What I insist on for high-current inverter installs:

- Proper DC fuse or breaker close to the battery (protect the cable, not the inverter).

- Correct cable gauge for the current and distance, with quality lugs and crimping.

- Solid grounds and clean bonding points (paint and corrosion ruin connections).

- Ventilation for the inverter—heat kills performance and reliability.

Internal link note: your installation guide belongs right here. Follow my RV inverter install checklist.

8) The 7 mistakes that cause shutdowns

If you want the “why does it keep tripping?” checklist, here it is:

- 1) You sized by marketing watts instead of real loads and surge behavior.

- 2) You ignored inverter surge wattage duration and assumed all surges are equal.

- 3) Your battery bank can’t supply the amps without sagging below cutoff.

- 4) Your cables are too small or too long (voltage drop steals performance).

- 5) Your connections are mediocre (heat at terminals = voltage loss + danger).

- 6) You stacked loads unintentionally (microwave + coffee maker + charger swarm).

- 7) You chose the wrong waveform and your appliance misbehaves or draws weirdly.

Fix these in order. Don’t shotgun upgrades. Measure, adjust, then upgrade. If you can only do one measurement, check battery voltage at the inverter terminals during a heavy load. If it dips hard, you found the real problem.

9) FAQ

What size inverter do I need for my RV?

Pick the worst-case realistic combo: largest load + surge + a few “always on” items. Many people do fine at 2000W pure sine for general use. If you want more flexibility (or a heavier microwave scenario), 3000W gives margin and fewer nuisance trips.

Why does my inverter trip when the wattage seems under the limit?

Three usual suspects: startup surge, voltage sag under load, or undersized wiring. Your inverter sees the total demand plus inefficiency, and it hates low voltage. I fix wiring and battery support first because a bigger inverter won’t cure a weak foundation.

Do I really need a pure sine inverter RV?

If you run a microwave, chargers, medical devices, or anything picky, yes. Modified sine can run some loads, but it can cause heat, noise, and device weirdness. Pure sine reduces edge cases and protects expensive electronics.

Can I run an RV air conditioner from an inverter?

You can, but you need the right combo: soft start, big pure sine inverter, and a battery bank that can deliver high current without sagging. If you’re missing any one of those pieces, you’ll see trips, short runtimes, or battery abuse.

What matters more: inverter size or battery capacity?

Inverter size decides what you can turn on. Battery capacity (and discharge ability) decides how long you can keep it on without sagging and tripping. Treat them like a matched pair, not separate purchases.

My Top Recommended Gear

- Pure sine wave inverter 3000W (RV-ready search)

- 4/0 AWG inverter cable kit (short run, high current)

- RV air conditioner soft start module (for inverter for AC)

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate and ClickBank Partner, I may earn a commission from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you.