Proper RV solar system design isn’t about buying the biggest panels or the flashiest components. It’s about understanding your actual energy consumption, matching your harvest potential to your lifestyle, and building a system that works seamlessly whether you’re boondocking in the Sonoran Desert or parked under pine trees in Oregon.

This guide is going to fix that knowledge gap. No fluff. No affiliate-driven recommendations for garbage products. Just the systematic approach I use with every client, broken down so you can do it yourself.

What Is RV Solar System Design (And Why Most Get It Wrong)

RV solar system design is the systematic process of calculating your electrical needs, then selecting and sizing solar panels, batteries, charge controllers, and inverters to create a self-sufficient power system. Done correctly, it provides reliable off-grid power. Done poorly, it creates an expensive lesson in electrical frustration.

The problem is that most RVers approach solar backwards. They start by asking “how many watts do I need?” when they should be asking “how many watt-hours do I consume?”

Those are completely different questions.

Watts measure instantaneous power draw. Watt-hours measure energy consumption over time. Your coffee maker might pull 900 watts, but if you only use it for 10 minutes, that’s just 150 watt-hours. Meanwhile, your 12V fridge running all day at 40 watts consumes 960 watt-hours. The fridge matters more than the coffee maker, despite the smaller wattage number.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, understanding watt-hour consumption is fundamental to any solar sizing calculation. Yet most kit manufacturers completely ignore this, slapping “perfect for RVs” on packages that couldn’t sustain a weekend warrior’s actual lifestyle.

The goal here is to give you a complete solar audit worksheet mentality—a systematic approach to measuring, calculating, and designing a system that actually works for YOUR specific situation.

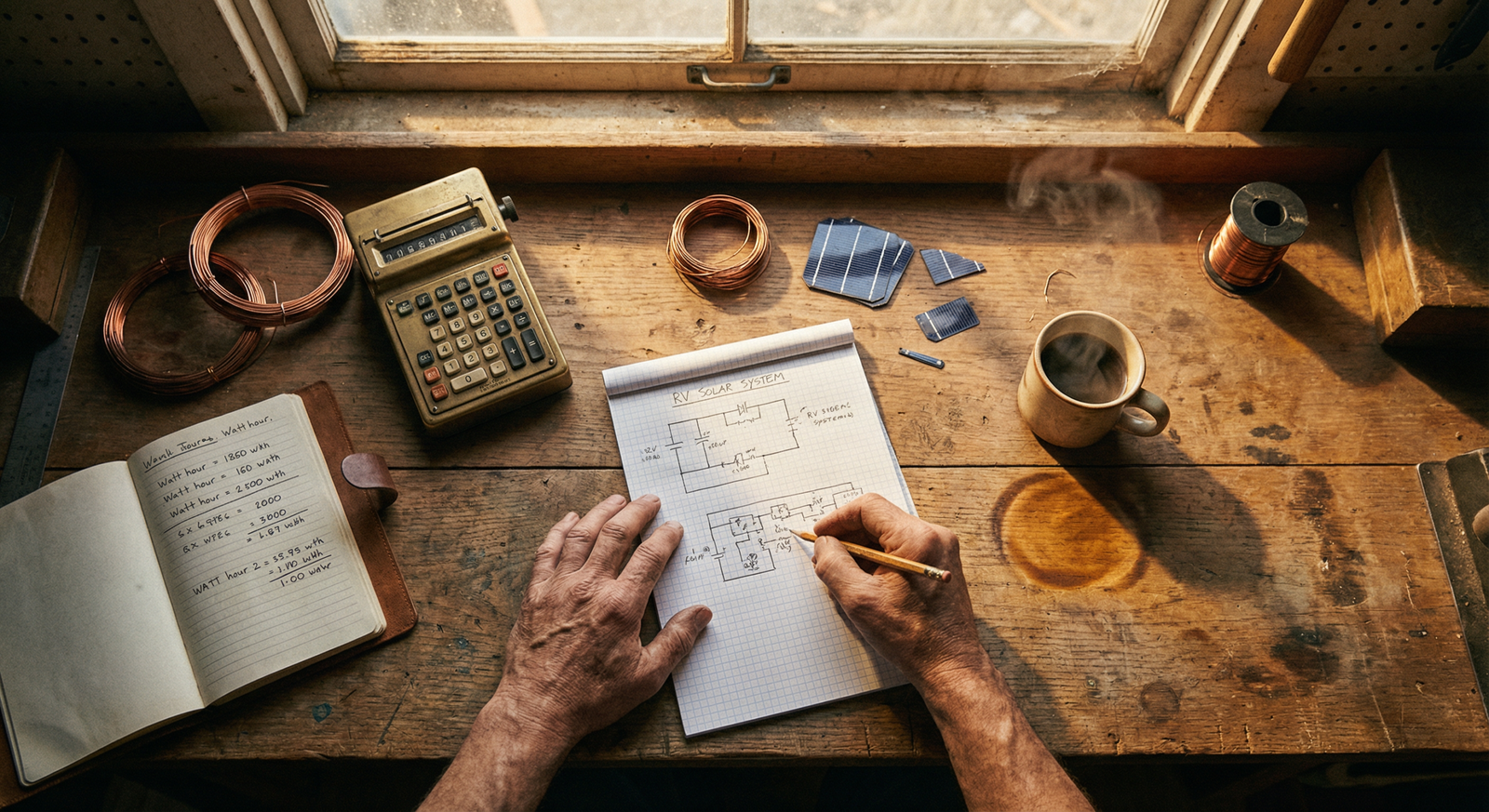

Step 1: The Energy Audit Nobody Wants to Do

This is where 90% of DIYers check out. They want the sexy stuff—panels, lithium batteries, shiny inverters. They don’t want to sit down with a notebook and a Kill-A-Watt meter.

Too bad. This step is non-negotiable.

Your solar audit worksheet needs to capture every device that draws power, how many watts it consumes, and how many hours per day you’ll use it. Here’s what that looks like in practice:

| Device | Watts | Hours/Day | Wh/Day |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12V Compressor Fridge | 45 | 12 (duty cycle) | 540 |

| LED Lighting (total) | 20 | 5 | 100 |

| Laptop | 60 | 4 | 240 |

| Phone Charging (x2) | 15 | 3 | 45 |

| Fan (Maxxair type) | 25 | 8 | 200 |

| Water Pump | 55 | 0.5 | 28 |

| TOTAL | — | — | 1,153 Wh |

Now here’s the critical insight: add 20-25% to that number for system inefficiencies. Your inverter loses some power as heat. Your charge controller isn’t 100% efficient. Wiring has resistance. So that 1,153 Wh becomes roughly 1,400-1,440 Wh of actual solar harvest required.

Many RVers use an RV solar calculator online to speed this up. They’re useful as a starting point, but they often make optimistic assumptions about sun exposure and component efficiency. Trust, but verify.

One more thing: if you’re navigating to remote boondocking spots, make sure you have a dedicated RV GPS that won’t lead you down roads your rig can’t handle. Nothing ruins an off-grid solar test like getting stuck on a logging road because Google Maps lied to you.

Step 2: Sizing Your Battery Bank Correctly

Here’s the truth about sizing RV solar panel battery systems: most people undersize their batteries while oversizing their panels. That’s exactly backwards.

Your battery bank is your energy savings account. Solar panels are just your income. Having a fat paycheck doesn’t help if you’ve got a checking account that can only hold fifty bucks.

The Math That Matters

Take your daily watt-hour consumption (including that 20% buffer) and decide how many days of autonomy you want. Autonomy means how long you can survive on batteries alone during cloudy weather or when parked in shade.

For most boondockers, 1.5 to 2 days of autonomy is the sweet spot. Less than that, and one rainy day has you running a generator. More than that, and you’re paying for battery capacity you’ll rarely use.

Using our example: 1,440 Wh/day × 2 days = 2,880 Wh of usable capacity needed.

Now here’s where battery chemistry matters enormously:

- Lead-acid (flooded or AGM): You can only safely use 50% of rated capacity without destroying the batteries. So you’d need 5,760 Wh (about 480 Ah at 12V) of rated capacity to get 2,880 Wh usable.

- Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4): You can safely use 80-90% of capacity. That same 2,880 Wh usable only requires about 3,200-3,600 Wh rated capacity (267-300 Ah at 12V).

Lithium costs more upfront but delivers 3-4x the cycle life and nearly double the usable capacity per pound. For anyone planning serious off-grid time, it’s not even a debate anymore.

I’ve installed hundreds of systems now, and the Renogy 100Ah LiFePO4 battery remains one of the most reliable mid-range options I recommend. Not the absolute cheapest, not the fanciest with unnecessary features, just solid performance with a legitimate BMS.

The Lead-Acid Trap

I need to say this clearly: AGM batteries are not a good investment for RV solar in 2024.

Yes, they’re cheaper upfront. But you’ll replace them in 2-4 years with heavy cycling, you can only use half the capacity, they’re heavy as sin, and they require more solar wattage to charge properly. When you factor in the total cost of ownership, lithium wins every time for anyone doing more than occasional weekend trips.

The only exception is if you’re doing a budget build on a rig you won’t keep long. Then AGM makes financial sense. Otherwise, save longer and buy lithium once.

Step 3: Sizing Your Solar Panels

Finally—the panels. Here’s the formula that actually works:

Daily Wh needed ÷ Peak Sun Hours = Minimum Panel Wattage

Peak sun hours aren’t the same as daylight hours. They represent the equivalent hours of full 1000W/m² solar intensity. According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), most of the continental US averages between 4-6 peak sun hours daily, with significant seasonal and geographic variation.

For conservative planning, use 4-5 hours. Let’s use 4.5 for our example:

1,440 Wh ÷ 4.5 hours = 320 watts minimum

Now add at least 25% for real-world conditions: panels get hot (reducing output), they get dirty, shadows from roof equipment create problems, and your angle to the sun is rarely optimal on an RV roof. That 320W becomes 400W for realistic planning.

Panel Types: Cut Through the Marketing

Monocrystalline: The standard choice. Highest efficiency, best performance in heat, slightly smaller footprint per watt. This is what you should buy unless you have a specific reason not to.

Polycrystalline: Cheaper, slightly lower efficiency, slightly worse heat performance. The savings aren’t worth it on an RV where roof space is limited.

Flexible panels: Lightweight and can conform to curved surfaces. They also overheat easily, have shorter lifespans, and can’t be tilted toward the sun. Avoid them unless weight is your absolute primary constraint (think overloaded van builds or popup campers).

Bifacial panels: Newer technology that captures reflected light on the back side. Interesting for ground-mounted applications but mostly marketing hype for roof-mounted RV installations where there’s nothing to reflect.

Series vs. Parallel Wiring

Quick primer that trips up a lot of DIYers:

- Series wiring (connecting positive to negative) adds voltages together. Two 12V panels in series = 24V input. Higher voltage means you can use smaller wire gauge and reduces voltage drop over long runs. Works great with MPPT controllers.

- Parallel wiring (connecting positive to positive, negative to negative) keeps voltage the same but adds current. More forgiving with partial shading but requires heavier wiring.

For most RV installations, series wiring with an MPPT controller is the way to go. Higher voltage input means better performance in suboptimal conditions and simpler wiring.

Step 4: Choosing the Right Charge Controller

The charge controller regulates power flow from panels to batteries, preventing overcharging and optimizing the charging process. There are two types that matter:

PWM (Pulse Width Modulation)

Simple, cheap, and inefficient. PWM controllers essentially waste the difference between your panel voltage and battery voltage. If your panels produce 18V and your battery needs 14.4V, that extra voltage becomes heat. You lose 15-25% of potential harvest compared to MPPT.

When PWM makes sense: Small systems under 200W where cost matters more than efficiency, or as a backup controller. That’s about it.

MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking)

MPPT controllers actively find the optimal voltage/current combination from your panels, then convert it efficiently to the appropriate battery charging voltage. They harvest 15-30% more power than PWM in real-world conditions.

The investment pays for itself. An MPPT controller might cost $100-200 more than PWM, but that extra 20% harvest means your 400W of panels perform like 480W. You’d spend more than that on the extra 80W of panels.

Sizing Your Controller

Controllers are rated for maximum input voltage, maximum output current, and maximum wattage. You need to check all three:

- Input voltage: Calculate your panel string’s maximum voltage (Voc rating × number in series) and ensure it’s below the controller’s max input. Cold weather increases voltage, so build in margin.

- Output current: Your total panel wattage divided by system voltage (usually 12V or 24V) gives you the output current. A 400W system on 12V needs at least a 33A controller (400÷12=33.3A).

- Wattage rating: Many controllers list a maximum wattage. Don’t exceed it, obviously.

Victron and Epever make excellent MPPT controllers. The Victron SmartSolar line adds Bluetooth monitoring, which is genuinely useful for troubleshooting and optimization. The Epever Tracer series offers comparable performance at lower cost.

Step 5: Inverter Selection (Where People Blow Their Budget)

The inverter converts 12V (or 24V) DC battery power to 120V AC household power. It’s also where I see the most wasted money and the most questionable decisions.

Do You Even Need AC Power?

Seriously. Before buying any inverter, audit what actually requires 120V AC:

- Most laptops can charge via USB-C PD or 12V car adapters

- Phone/tablet charging is USB

- LED lighting should be 12V

- 12V refrigerators are more efficient than AC models

- Fans run fine on 12V

Many RVers buy 2000W or 3000W inverters and use 10% of that capacity. Every watt of inverter capacity costs money, adds weight, and most importantly, all inverters consume power just being turned on (parasitic draw). A big inverter might pull 15-30W just idling.

When You Do Need an Inverter

Size it for your realistic needs. A dedicated coffee maker user needs maybe 1000W. Someone running power tools occasionally needs 2000W. Only if you’re running an air conditioner off solar do you need 3000W+.

Pure sine wave vs. modified sine wave: Pure sine wave is the only option in 2024. Modified sine wave inverters cause problems with sensitive electronics, make motors run hot, and create an annoying buzzing in audio equipment. The price gap has narrowed enough that there’s no reason to compromise.

Inverter-chargers combine an inverter with a shore power charger and automatic transfer switch. They cost more but simplify wiring and provide seamless switchover between solar/battery power and shore power. For full-timers or serious boondockers, they’re worth considering.

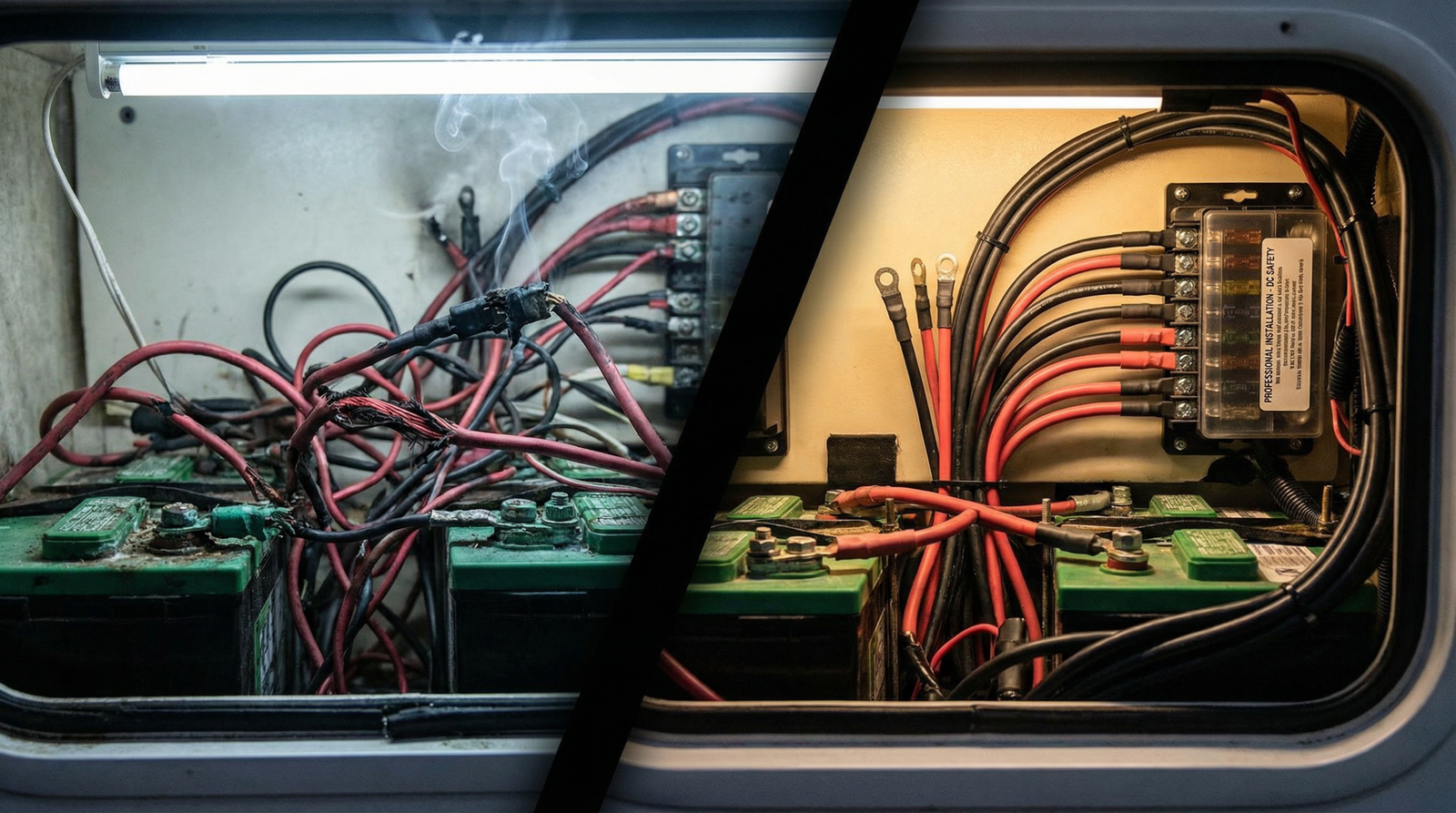

Step 6: Wiring—The Boring Stuff That Matters Most

I’ve seen systems with $2,000 worth of beautiful components connected with dollar-store wire. The panels are perfect, the batteries are top-tier, and the whole setup runs like garbage because nobody bothered to size their conductors properly.

Voltage drop is the silent killer of RV solar performance.

When current flows through undersized wire, it creates resistance. Resistance causes voltage drop. Voltage drop means less power reaching your batteries and heat building in your wiring. The physics of voltage drop are straightforward: longer runs and higher currents require thicker wire.

Wire Sizing Guidelines

Target 3% or less voltage drop for any run. Here’s a simplified chart for 12V systems:

| Current (Amps) | 10 ft run | 15 ft run | 20 ft run |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10A | 12 AWG | 10 AWG | 10 AWG |

| 20A | 10 AWG | 8 AWG | 6 AWG |

| 30A | 8 AWG | 6 AWG | 4 AWG |

| 50A | 6 AWG | 4 AWG | 2 AWG |

Battery-to-inverter connections are critical. A 2000W inverter at 12V can pull 175+ amps during surge loads. That needs 2/0 or 4/0 cable for typical RV installations. Skimp here and you’ll either have performance problems or a fire—neither is acceptable.

Fusing and Overcurrent Protection

Every positive conductor needs appropriate fuse protection. This isn’t optional—it’s basic electrical safety.

- Solar panels to charge controller: fuse near the panels, sized for cable capacity

- Charge controller to battery: fuse near the battery, sized for maximum controller output

- Battery to inverter: Class T or ANL fuse as close to the battery as possible

- Individual 12V circuits: blade fuses at a distribution panel

Use marine-grade tinned copper wire for anything that might see moisture or vibration. Yes, it costs more. Yes, it matters. Your standard automotive wire will corrode at connections and fail at inopportune times.

The 7 Deadly Sins of DIY RV Solar

After a decade in this business, I’ve catalogued the recurring failures. Here they are, ranked by how often they cause regret:

1. Underestimating the Battery Bank

Everyone does this. They buy 200W of panels and a single 100Ah battery, then wonder why they can’t run their stuff overnight. Your battery bank should typically be larger than your daily consumption, not smaller.

2. Ignoring Shade Impacts

That AC unit, vent fan, and antenna casting shadows across your panels? Each shaded cell can drag down an entire panel’s output—sometimes the whole string if wired in series without bypass diodes. Map your shadows before finalizing panel placement.

3. Cheaping Out on the Charge Controller

A $30 PWM controller on a $1,500 panel array is false economy. Spring for MPPT.

4. Using House Extension Cords for High-Current Connections

I’ve seen this. Actual household extension cords running from inverters to batteries. Just… don’t. Use proper cable with properly crimped ring terminals.

5. No Monitoring System

Flying blind means you won’t know you have a problem until your batteries are damaged. At minimum, get a battery monitor that shows voltage, current, and state of charge. Victron’s SmartShunt is excellent for this.

6. Mounting Panels Flat When They Could Be Tilted

A tilted panel toward the sun can produce 20-30% more power than a flat-mounted panel. Tilt mounts add cost and complexity, but they significantly improve harvest—especially in winter or northern latitudes.

7. Forgetting About Temperature

Lithium batteries don’t like charging below freezing—their BMS should prevent it, but cold charging damages cells. If you’re a four-season camper, you need batteries with low-temperature cutoffs or built-in heating.

Real-World System Examples

Theory is great. Let’s look at actual systems for different use cases:

The Weekend Warrior (600-800 Wh/day)

- 200W solar panels (single or 2×100W)

- 100-200Ah LiFePO4 battery

- 20A MPPT charge controller

- Optional: 1000W inverter

- Budget: $800-1,200

This handles LED lights, phone/laptop charging, a 12V fridge, and occasional small AC loads. Enough for Friday-to-Sunday trips without hookups.

The Serious Boondocker (1,200-1,600 Wh/day)

- 400-500W solar panels

- 300-400Ah LiFePO4 battery

- 40A MPPT charge controller

- 2000W pure sine inverter

- Budget: $2,500-4,000

This supports extended dry camping with moderate creature comforts. Coffee maker, laptop work, bigger fridge, and occasional power tools. This is the system I recommend most often.

The Full-Time Off-Gridder (2,000-3,000+ Wh/day)

- 800-1200W solar panels (possibly with ground-deployed portable panels)

- 600-800Ah LiFePO4 battery (24V system recommended)

- 60A+ MPPT charge controller

- 3000W inverter-charger

- DC-DC charger for alternator charging

- Budget: $6,000-12,000+

This approaches true energy independence. Air conditioning is possible on the best sun days, you can run residential-style appliances, and extended cloudy spells won’t strand you.

Final Thoughts from the Field

Here’s the bottom line on RV solar system design: the math isn’t hard, but you have to actually do it.

Every failed system I’ve seen stems from skipping the energy audit, ignoring the relationship between batteries and panels, or cutting corners on components that seem boring but matter enormously—like wiring and charge controllers.

Start with your consumption. Be honest about it. Use a Kill-A-Watt, run your numbers, and build your worksheet. From there, size your batteries for real-world autonomy, then size your panels to refill those batteries in realistic sun conditions. Choose an MPPT controller that matches your panel configuration. Size your inverter for actual needs, not theoretical maximums. Wire everything properly with appropriate fuses.

Do those things in that order, and you’ll have a system that works reliably for years. Skip steps or work backwards from “I want 400 watts of panels,” and you’ll be troubleshooting forever.

The best RV solar calculator is the one between your ears, fed with accurate information about your specific situation. No YouTube personality or online quiz can substitute for understanding your own rig and lifestyle.

Now stop researching and start measuring. That energy audit isn’t going to complete itself.

— See you out there, somewhere with good sun exposure and no hookups.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

One Comment